Monthly Features Archive

CULT

HOLLYWOOD HEROES: CULT

HOLLYWOOD HEROES:

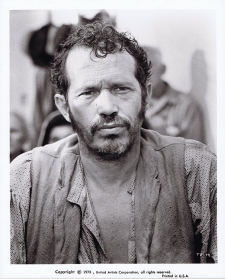

Warren Oates

1928-1982

Best known for his performances in the films of Sam

Peckinpah, Warren Oates carved out a memorable career

playing a variety of offbeat roles with an astonishing

range. Relegated to supporting roles for the most part, he

landed starring roles in a number of 1970s films such as

"Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia" and "Two Lane

Blacktop" that have assured him of something more than cult

status. Today, the actor is remembered for his wide range of

colorful outsider characters. His uncommon, alternately

crude and loveable persona is admired by directors such as

Quentin Tarrantino and Richard Linklater.

Warren Mercer Oates was born in rural Kentucky in 1928,

where his father owned a general store. He began his acting

career in the Mid-1950s after a stint in the Marines. For

six years he appeared in a variety of television shows

including "Playhouse 90," "Have Gun Will Travel" and "Wagon

Train." While working on the television on show "The

Rifleman" he met director Sam Peckinpah who was also serving

his apprenticeship. With the popularity of the western

feature beginning to fade, Peckinpah would direct one of the

last great westerns of the classic era, "Ride the High

Country" in 1962, giving Oates a defining role as one of the

scurvy Hammond brothers. Oates would go on to appear in

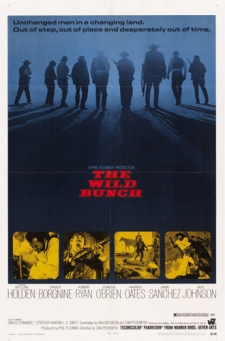

three more of his films including "The Wild Bunch" and

"Major Dundee".

In addition to his acting for Peckinpah, Oates worked with

many other top directors of the era, including Joseph L.

Mankiewicz in "There Was a Crooked Man," Terence Mallick in

"Badlands" and Norman Jewison in "In the Heat of the Night",

memorably playing a racist police officer. He then went on

to a brief career as a l eading

man in film such as "Dillinger," "Race With the Devil" and "Cockfighter."

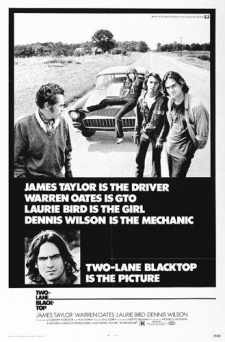

"Two Lane Blacktop," a film by frequent collaborator Monte

Hellman, was a box office disappointment at the time, but

has since become a cult favorite in a large part due to

Oates performance as an aging hot rodder. His final years

found him working in "A" budget films with directors like

Stephen Spielberg ("1941") and Ivan Reitman ("Stripes"). eading

man in film such as "Dillinger," "Race With the Devil" and "Cockfighter."

"Two Lane Blacktop," a film by frequent collaborator Monte

Hellman, was a box office disappointment at the time, but

has since become a cult favorite in a large part due to

Oates performance as an aging hot rodder. His final years

found him working in "A" budget films with directors like

Stephen Spielberg ("1941") and Ivan Reitman ("Stripes").

Oates died of a heart attack in 1982; his final movies

released posthumously. Today, the actor is remembered for

his wide range of colorful outsider characters.

James Cagney

Of

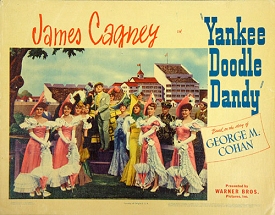

all his movies, perhaps surprisingly, Cagney’s favorite was

Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942). The urban-centric, rough-necked

image portrayed in his gangster movies was in fact, unlike

him. “Though I soon became typecast in Hollywood as a

gangster and hoodlum, I was originally a dancer, an Irish

hoofer, trained in vaudeville tap dance. I always leapt at

the opportunity to dance in films later on.” He spent as

much time as possible on his farm, away from the bright

lights of Hollywood; someone more comfortable with a shovel

in hand than a pistol. This, if anything, makes his

convincing hoodlum manner all the more impressive. Of

all his movies, perhaps surprisingly, Cagney’s favorite was

Yankee Doodle Dandy (1942). The urban-centric, rough-necked

image portrayed in his gangster movies was in fact, unlike

him. “Though I soon became typecast in Hollywood as a

gangster and hoodlum, I was originally a dancer, an Irish

hoofer, trained in vaudeville tap dance. I always leapt at

the opportunity to dance in films later on.” He spent as

much time as possible on his farm, away from the bright

lights of Hollywood; someone more comfortable with a shovel

in hand than a pistol. This, if anything, makes his

convincing hoodlum manner all the more impressive.

Somewhat

more bizarrely, he was only forced into doing the patriotic

sing-a-long because of accusations made claiming he was a

communist. The controversy caused him to do everything in

his power to make a film that would convince people once and

for all where his heart lay. This for Cagney was pure luck.

He quickly shook the shackles of his stellar performance in

The Public Enemy. After years of sharp shooting and hanging

out with the filthy deadbeats of society, Cagney was in his

element: singing and dancing. Somewhat

more bizarrely, he was only forced into doing the patriotic

sing-a-long because of accusations made claiming he was a

communist. The controversy caused him to do everything in

his power to make a film that would convince people once and

for all where his heart lay. This for Cagney was pure luck.

He quickly shook the shackles of his stellar performance in

The Public Enemy. After years of sharp shooting and hanging

out with the filthy deadbeats of society, Cagney was in his

element: singing and dancing.

He was always a pleasure to watch, an actor who used his

most powerful tool, his eyes, to

great

effect. Not since Peter Lorre had an audience been so

mesmerized. He had eyes that you would quickly glance away

from on the street, if you ever had the misfortune of

meeting them. However, as opposed to Lorre, the audience was

not filled with fear or suspense; rather, they were excited.

You knew whoever was in the lock of those eyes was surely

doomed, and you waited eagerly for that boom-boom-bang. I

always felt that Cagney was the kind of guy you would end up

thanking for slapping you in the face, probably out of

respect. He set the tone for Napoleonic angry men, who would

resurface at various intervals in the timeline of cinema;

famous examples being Al Pacino and Joe Pesci. great

effect. Not since Peter Lorre had an audience been so

mesmerized. He had eyes that you would quickly glance away

from on the street, if you ever had the misfortune of

meeting them. However, as opposed to Lorre, the audience was

not filled with fear or suspense; rather, they were excited.

You knew whoever was in the lock of those eyes was surely

doomed, and you waited eagerly for that boom-boom-bang. I

always felt that Cagney was the kind of guy you would end up

thanking for slapping you in the face, probably out of

respect. He set the tone for Napoleonic angry men, who would

resurface at various intervals in the timeline of cinema;

famous examples being Al Pacino and Joe Pesci.

Locations in Hollywood Cinema:

The Diner

The

diner is a symbol of America. Its twenty-four hour nature

and endless menu symbolize the countries’ commitment to give

people as much freedom as possible to do as much of what

they please. It is not surprising then that cinema has

chosen the diner as a location that draws those who desire

to do exactly what they want, without concern for others.

Serial killers, punks, hoodlums and drunks, are but a few of

the patrons in any movie diner; sitting next to students,

teachers, miners and preachers. They choose this explicitly

public place, this icon of Americana, to leap from the

confines of normal social behavior. As the gathering place

for all of suburban America, the diner has been chosen

repeatedly in American cinema to reveal the countries’ more

sinister side. The

diner is a symbol of America. Its twenty-four hour nature

and endless menu symbolize the countries’ commitment to give

people as much freedom as possible to do as much of what

they please. It is not surprising then that cinema has

chosen the diner as a location that draws those who desire

to do exactly what they want, without concern for others.

Serial killers, punks, hoodlums and drunks, are but a few of

the patrons in any movie diner; sitting next to students,

teachers, miners and preachers. They choose this explicitly

public place, this icon of Americana, to leap from the

confines of normal social behavior. As the gathering place

for all of suburban America, the diner has been chosen

repeatedly in American cinema to reveal the countries’ more

sinister side.

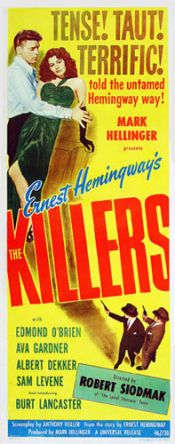

The opening scene from 1946’s The Killers takes place in

a run-of-the-mill New Jersey diner. Two hired guns enter the

diner, disrespect the owner, tie and gag the cook and only

other customer, then wait guns at the ready, for a regular

patron to walk through the front door. As the killers sit

patiently the nonchalant regularity and calmness of their

actions seems to suggest that this occurrence could happen

on any given night at this diner, and not just this

Brentwood, NJ diner but any one of them across the country.

Because of their mundane feel

and

transferable itinerancy it is easy to see the diner as a

location of national symbolism. Their furniture is similar,

their waitresses dress alike, and they all have photos of

Buddy Holly on the wall. The collective dinginess of all

these establishments creates shadows for the dregs of

society to operate in; they are the playgrounds of society

before the bars open, and after the barman’s gone home. and

transferable itinerancy it is easy to see the diner as a

location of national symbolism. Their furniture is similar,

their waitresses dress alike, and they all have photos of

Buddy Holly on the wall. The collective dinginess of all

these establishments creates shadows for the dregs of

society to operate in; they are the playgrounds of society

before the bars open, and after the barman’s gone home.

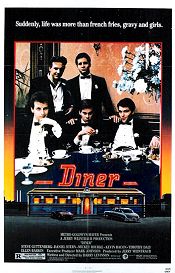

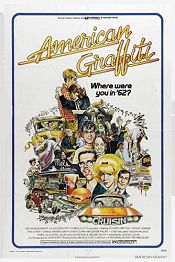

Perhaps the high points of the diner’s role in cinema

comes when those social dregs step out the shadows and

disturb (sometimes gravely) the rest of the good, honest, paying

customers. Oliver Stone chose the diner as the location for

Mickey and Mallory’s murderous coming-out party location in

1994’s Natural Born Killers. As truckers, those with

mischief or murder on the mind, those who have nowhere else

to go, or those who simply need a coffee or some bacon,

gather and mingle many violent climaxes have been reached in

American cinema history. The Diner, American Graffiti, and

Pulp Fiction all used the diner as a location, and in seldom

few films was it a pleasant one. They are usually motionless

places of regularity, with Hopper-like nighthawks

frequenting them throughout the night. Yet, every so often

they are the witness to explosive levels of rage and

violence, after all what better place to announce your

criminal intent to the town than in the modern day version

of the Wild West salon: The Diner.

(sometimes gravely) the rest of the good, honest, paying

customers. Oliver Stone chose the diner as the location for

Mickey and Mallory’s murderous coming-out party location in

1994’s Natural Born Killers. As truckers, those with

mischief or murder on the mind, those who have nowhere else

to go, or those who simply need a coffee or some bacon,

gather and mingle many violent climaxes have been reached in

American cinema history. The Diner, American Graffiti, and

Pulp Fiction all used the diner as a location, and in seldom

few films was it a pleasant one. They are usually motionless

places of regularity, with Hopper-like nighthawks

frequenting them throughout the night. Yet, every so often

they are the witness to explosive levels of rage and

violence, after all what better place to announce your

criminal intent to the town than in the modern day version

of the Wild West salon: The Diner.

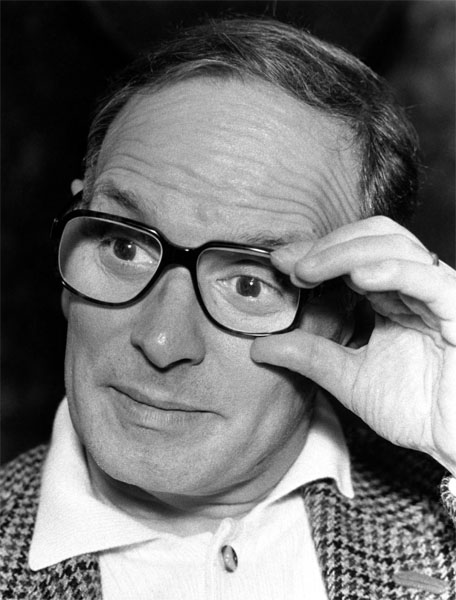

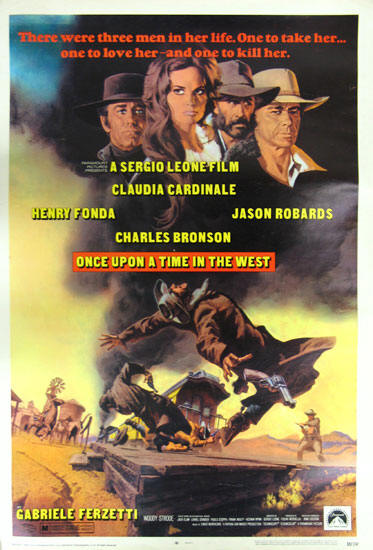

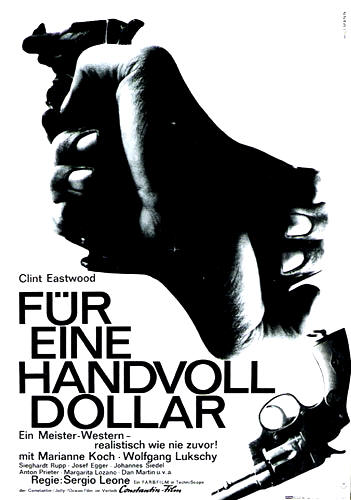

Ennio Morricone Musico!

Ennio

Morricone was born in Roma in 1928, and can, some 80 years

later, be considered a man who changed not just his niche of

the film industry (music), but also the production of movies

in general. His scores, perhaps more so than any other

composer, show us how much music can add to movies. His

influence spreads far and wide, from Eastwood to Metallica,

who are said to start their shows with an instrumental of Il

Buono, il brutto, il cattivo’s ‘The Ecstasy Of Gold’.

Intensity, humor, suspense and drama; all aspects which

amplify when Morricone assembled the music. He arranged the

music behind many of the Spaghetti Westerns, especially

those of school friend Sergio Leone, yet also took time out

to emphasize his w Ennio

Morricone was born in Roma in 1928, and can, some 80 years

later, be considered a man who changed not just his niche of

the film industry (music), but also the production of movies

in general. His scores, perhaps more so than any other

composer, show us how much music can add to movies. His

influence spreads far and wide, from Eastwood to Metallica,

who are said to start their shows with an instrumental of Il

Buono, il brutto, il cattivo’s ‘The Ecstasy Of Gold’.

Intensity, humor, suspense and drama; all aspects which

amplify when Morricone assembled the music. He arranged the

music behind many of the Spaghetti Westerns, especially

those of school friend Sergio Leone, yet also took time out

to emphasize his w ork

in other genres: “I'm not linked to one genre or another. I

like to change, so there's no risk of getting bored.” ork

in other genres: “I'm not linked to one genre or another. I

like to change, so there's no risk of getting bored.”

Within his field he is greatly appreciated, as needs

require. In his long career, he has received many awards:

the Golden Lion and the Honorary Oscar, among which 8 Nastri

D’argento, 5 Baftas, 5 Oscar Nominations, 7 David Di

Donatello, 3 Golden Globes, 1 Grammy Award and 1 European

Film Award. In the 2009 the President of the French

Republic, Nicolas Sarkozy, has signed a decree giving him

the rank of Knight in the Order of the Legion of Honor. If

we fail to recognize Morricone’s genius, we may fail to see

how much a musical score can add to a film. Even silent

films, many of which are shown today with musical

accompaniment, can benefit from music.

Of all the genres, it is horror that benefits most from

music. The sounds can be used not only to build suspense as

the inevitability of the killing becomes apparent, but also

to add to the intensity of the climatic killing. Dario

Argento’s Suspiria is filled for the first half hour with a

plethora of peculiar sounds, all of which add to the nervous

feeling the viewer has, when they know that someone will

surely die. Perhaps then it is a shame that Morricone was

not so involved in horror movies. Regardless, his legacy as

a musician and film contributor will life on eternally, and

hopefully be added to in the coming years.

JIMMY STEWART: AMERICA’S ACTOR

Jimmy

Stewart is one of America’s best-loved and finest actors.

His career spanned nearly 60 years, and included a wide

variety of roles. He can be regarded as a Western star, a

leading man in thrillers, or as the quintessential American

family man. His amiability on screen was equaled off screen

where he was an impressively decorated veteran, and pioneer

for black and white films. Jimmy

Stewart is one of America’s best-loved and finest actors.

His career spanned nearly 60 years, and included a wide

variety of roles. He can be regarded as a Western star, a

leading man in thrillers, or as the quintessential American

family man. His amiability on screen was equaled off screen

where he was an impressively decorated veteran, and pioneer

for black and white films.

He held the highest active military rank of any actor in

history. During World War II, he served in the Army Air

Corps and rose to the rank of colonel. This bravery as a

soldier was not matched by some of his more “macho”

co-stars, in particular John Wayne, who has a reputation as

a recruitment dodger.

One image that is easy to picture is of Stewart and best

friend Henry Fonda settling down to their favorite activity

of silently painting model airplanes together.

In this day and age of actors who more frequently makes

us roll our eyes than inspire us; Stewart would be a simple

and welcome change. He was liked in many sectors of society,

for example Former President Harry S. Truman, who was once

quoted as saying that if he had a son, he would want them to be just

like “just like Jimmy Stewart;” and while always gracious

with his fans, he was always very protective of his privacy.

A notable example of this occurred when a nervy family of

tourists set up a picnic on his front lawn. Stewart came out

of his house and, without uttering a word, turned on the

sprinklers. It is nice that an actor of such talent didn’t

have the pretensions to match: “I'm the inarticulate man who

tries. I don't really have all the answers, but for some

reason, somehow, I make it.”

saying that if he had a son, he would want them to be just

like “just like Jimmy Stewart;” and while always gracious

with his fans, he was always very protective of his privacy.

A notable example of this occurred when a nervy family of

tourists set up a picnic on his front lawn. Stewart came out

of his house and, without uttering a word, turned on the

sprinklers. It is nice that an actor of such talent didn’t

have the pretensions to match: “I'm the inarticulate man who

tries. I don't really have all the answers, but for some

reason, somehow, I make it.”

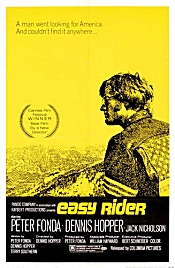

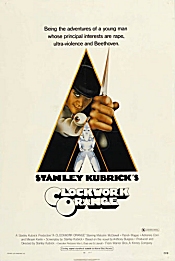

Film taglines

Film taglines are still used today, but only a few

studios

appreciate

their importance in film history, and appreciate how much we

need and love them. It takes a good tagline to hearken back

to a film, or to "reinforce that one iconic image. " If

creative, they can be powerful tools of advertisement. This

Monthly Feature recalls some of my personal favorites, and I

hope that by doing so; I can speak to the continued

importance of this niche of film advertising. appreciate

their importance in film history, and appreciate how much we

need and love them. It takes a good tagline to hearken back

to a film, or to "reinforce that one iconic image. " If

creative, they can be powerful tools of advertisement. This

Monthly Feature recalls some of my personal favorites, and I

hope that by doing so; I can speak to the continued

importance of this niche of film advertising.

Some are

great because of their simplicity, and ability to sum up a

film in one line:

1.

"Crushed lips don't talk." ('I Confess')

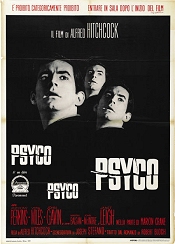

2. "Check in. Relax. Take a shower."

('Psycho')

3. "The film that will satisfy every over-sexagesimal

adult." ('Orgy of the Dead')…what, even moi?

4. "Being the adventures of a young man

whose principal interests are rape, ultra-violence and

Beethoven." ('A Clockwork Orange')

5. "Pathetic earthlings, who can save you

now?" ('Flash Gordon')…or Jack Bauer.

6. "They're tobacco chewin', gut chompin',

cannibal kinfolk from hell." ('Redneck Zombies')…bet you'll

rush out a see this film!

Yet other films choose to be

suggestive instead, trying to entice potential viewers with

peculiar statements, which generate more questions than

answers:

7. "From the moment they met, it was

murder." ('Double Indemnity')

8.

"A man went looking for America and couldn't find it

anywhere." ('Easy Rider') 8.

"A man went looking for America and couldn't find it

anywhere." ('Easy Rider')

9. "This was the weekend they didn't play golf."

('Deliverance')…this film must be the best advertisement for

golf ever.

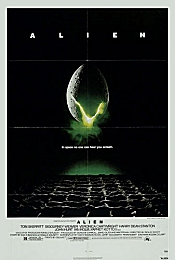

10. "In space no-one can hear you scream."

('Alien')…classic!

11. "Does for Rock and Roll what 'The Sound

of Music' did for hills." ('This is Spinal Tap!")

And now, because I'm very

self-important, my all time favorite:

"Hombre means man. Paul Newman is Hombre."

('Hombre')

Voyeurism: The Next

Level Of Creepiness

In

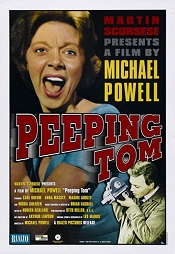

1960, Alfred Hitchcock and Michael Powell were two

of Britain’s most prominent filmmakers. Their

projects that year, although similar in theme and

content, received wildly opposing reactions from

moviegoers. ‘Peeping Tom’ sent Powell’s career into

a tailspin, rendering his earlier classics, ‘The Red

Shoes’ (1948), ‘Black Narcissus’ (1947), and ‘The

Thief of Baghdad’ (1940), as nothing more than

distant memories. ‘Psycho’, on the other hand, was a

commercial success, and Hitchcock went on to create

even more success stories. In

1960, Alfred Hitchcock and Michael Powell were two

of Britain’s most prominent filmmakers. Their

projects that year, although similar in theme and

content, received wildly opposing reactions from

moviegoers. ‘Peeping Tom’ sent Powell’s career into

a tailspin, rendering his earlier classics, ‘The Red

Shoes’ (1948), ‘Black Narcissus’ (1947), and ‘The

Thief of Baghdad’ (1940), as nothing more than

distant memories. ‘Psycho’, on the other hand, was a

commercial success, and Hitchcock went on to create

even more success stories.

Not

many like to be watched, but most like to watch.

Voyeurism alone is an unnerving phenomenon, but when

a filmmaker explores it, the creepiness reaches new

levels. Filmmakers’ dealing with voyeurism is

disturbing enough, given that they spend half their

lives behind cameras, watching. But when Alfred

Hitchcock and Michael Powell explored it in 1960

they went one step further; by inserting themselves

and their audiences into the mind of a voyeur, they

forced voyeurism as an issue. Not

many like to be watched, but most like to watch.

Voyeurism alone is an unnerving phenomenon, but when

a filmmaker explores it, the creepiness reaches new

levels. Filmmakers’ dealing with voyeurism is

disturbing enough, given that they spend half their

lives behind cameras, watching. But when Alfred

Hitchcock and Michael Powell explored it in 1960

they went one step further; by inserting themselves

and their audiences into the mind of a voyeur, they

forced voyeurism as an issue.

Hitchcock’s fascination with this phenomenon can

be seen in earlier films such as ‘Rear Window’, but

in ‘Psycho’ he chose to use a 50 mm lens on his 35

mm camera, which I am told, gives a closer

representation of human vision; thus enabling his

viewers to take part in the voyeuristic exploits of

Norman. We are unnerved upon meeting Anthony

Perkins’ character because of his eerie smile and

peculiar hobby of taxidermy (stuffing birds), but we

only find out about his sinister motives when he

peers through a hole in the wall at his motel

guests. In other words, we become enthralled by, and

afraid of Norman Bates, only when we learn he is a

voyeur.

Powell, far more disturbingly, used his family in

‘Peeping Tom’s’ bizarre home-movies: his wife plays

‘the successor’ to Mark’s mother, and his real-life

son plays the young Mark. In fact, Powell himself

plays the character of Mark’s Father, the most

voyeuristic and disturbing of all the film’s

players, and every camera that the film’s lead uses

is marked with the name ‘Michael Powell’, linking

the director to both members of the film’s

voyeuristic Father and Son duo. Although both

directors are interested in voyeurism, it is perhaps

this heightened level of personal inclusion by

Powell that makes ‘Peeping Tom’ that much more

unsettling. It could even be suggested that it was

this that prompted the film’s initial commercial

failure and controversy. Regardless, both films

offer an interesting insight into voyeurism, and do

so not by stepping back and observing it as a

psychological phenomenon, but rather by engrossing

the film in it, and exploring their own voyeuristic

fantasies, for us to observe.

Saul

Bass Saul

Bass

The style imprint of Saul Bass can still be seen

today in modern commercial advertising and graphic

design alike. The Art Director’s Club notes how

“it's virtually impossible for any North American to

pass through a day without encountering a Bass

design, artifact or image.” Granted, his title

sequences are rightly what he is renowned for, but

his contribution to movie poster has not gone

unnoticed, and he can easily claim to have changed

the art of film advertising and posters forever.

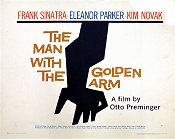

The

abstract, crooked hand, which the Half Sheet for

“The Man With The Golden Arm” centers around, is not

only striking, but also somewhat revolutionary. For

many years leading up to it, it was the stars that

were captured in the poster, and it is Bass whom we

are indebted to for this change. The

abstract, crooked hand, which the Half Sheet for

“The Man With The Golden Arm” centers around, is not

only striking, but also somewhat revolutionary. For

many years leading up to it, it was the stars that

were captured in the poster, and it is Bass whom we

are indebted to for this change.

Rather

than a poster glorifying the star, Frank Sinatra, we

have a work of graphic art. His influence has been

felt ever since in the world of movie posters,

inspiring an alternative approach to film marketing,

based more on aesthetics than reputation.

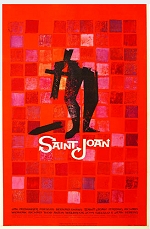

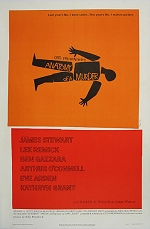

Perhaps his best design work comes in the US-One

Sheet for ‘Anatomy of a Murder’, where his

abstraction extends from the arm to the whole body,

giving an image that hearkens, in every beholder,

thoughts of criminal acts, crime cinema, and,

perhaps most importantly, graphic design: moving

movie posters one step closer to that much

sought-after title of ‘art’.

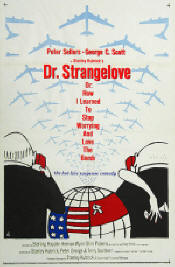

Gadget-Man Stan: The Use of

Machines in Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove and 2001: A Space

Odyssey

While

watching these two Kubrick classics the thing that stood out

for me was the long, detailed shots of machines. The

emphasis put on machines in Dr. Strangelove shows how

powerless man had become over what is man-made at that time

in history. Or, as Dr. Strangelove puts it the machines had

been designed to “rule out human meddling,” which in the end

leads to our total destruction. Ironically, with all those

gadgets General Ripper believes the Russians are poisoning

the water, an ancient way to bring-down societies. Further,

with all the gadgets available, man is still unable to

benefit from them because of their own failings. Captain

Mandrake struggles to use the phone to call the president

because of a suspicious officer, and the destroyed radio on

the Maj. Kong plane makes it impossible to recall the order

to fire on the Russians. While

watching these two Kubrick classics the thing that stood out

for me was the long, detailed shots of machines. The

emphasis put on machines in Dr. Strangelove shows how

powerless man had become over what is man-made at that time

in history. Or, as Dr. Strangelove puts it the machines had

been designed to “rule out human meddling,” which in the end

leads to our total destruction. Ironically, with all those

gadgets General Ripper believes the Russians are poisoning

the water, an ancient way to bring-down societies. Further,

with all the gadgets available, man is still unable to

benefit from them because of their own failings. Captain

Mandrake struggles to use the phone to call the president

because of a suspicious officer, and the destroyed radio on

the Maj. Kong plane makes it impossible to recall the order

to fire on the Russians.

Kubrick juxtaposes marveling in the beautiful majesty and

complexity of the machines, and showing how dangerous the

machines can potentially be. It seems to me that Kubrick was

at that time almost having an experience of numinous: he is

fascinated by the intricacy of the machines, but fears their

consequences. Regardless, like a mystic he must portray this

phenomenon that surrounds and confronts him and the 1960s

audience. Although the conversation between the two world

leaders shows how far we have come technologically, in that two people from opposing sides of the worlds can

speak as if face-to-face, but also shows how useless all

that technological development is if the people who are

using them are foolish, or drunk!

in that two people from opposing sides of the worlds can

speak as if face-to-face, but also shows how useless all

that technological development is if the people who are

using them are foolish, or drunk!

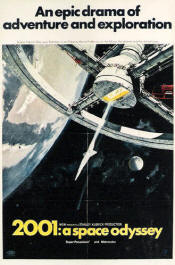

Timothy E. Scheurer sums up the relationship between man

and machine in 2001 by saying: "For all the science,

technology, and intellectual speculation about the

future…they are still primarily concerned with the human

condition and the reaffirmation of our humanity...Science

fiction traditionally has also been a site where the belief

in progress (especially scientific of technological

progress) comes up against a distrust of the very same

science and technology."

Perhaps the climax of this tense relationship comes not

as the world ends in Dr., since man is still somewhat to

blame there, but as 2001 ends with a computer that can

reason and destroy without the meddling of man. This may

well be Kubrick’s ultimate fear, as a machine is humanized

in the form of HAL 2009, with the calm, collected, but

moreover eerie voice of Douglas Rain. Kubrick shows us how

complex the machines are, but how easy it is for us fallible

human beings to suffer because of them.

|

|

|